Valyrio Bardion: Ligatures

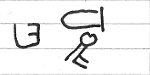

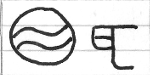

The last – and newest – element of High Valyrian writing are ligatures. Ligatures in this case means symbols designed as a short version for frequent combinations of phonograms. The easiest example would probably be “se”, a High Valyrian word for “and”, which looks like this:

Ligatures are used in two different cases: they’re either replacements for very complicated logograms, or they’re used to clarify logograms (or in other contexts), which wouldn’t have been written out before.

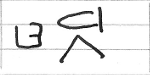

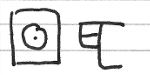

Originally, I imagine that High Valyrian was written with many more logograms that it is now. I used the example of “emagon” above, which is still used in combination with other logograms to create verbs derived from the first one. But most of these logograms are no longer used, presumably because they were complicated or so detailed that, while their use in inscriptions and temples and such was feasible, their use in written language was not. In those cases, they were at first replaced by phonetic writing, which then developed into new signs which were not ultimately based on pictorial representations, but on phonetic letters. Some examples for this would be suffixes like “-anna” or “-āzma”, or the prefix “nā-”. Some examples:

| bartanna | iāpanna | embāzma |

|

|

|

| udrāzma | nābēmagon | nāgeltigon |

|

|

|

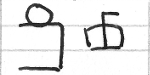

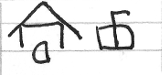

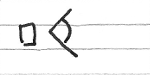

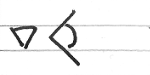

In the second case, one logogram was used to express several related words and it was not clear from the logogram itself, only the grammatical context, which one it was. Examples for this would be adjectives that were created from nouns, like “gēlion” and “gēlenka” or “embar” and “embōñe”. Of course, ligatures are only used if the difference between the two words that you want to distinguish from each other differ by more than one phoneme. If it’s only one phoneme, a phonogram is used, such as with “arlie” and “arlī” (and even in cases where the adverb ends in -irī, it is simply written as -ī), or “urnegon” and “jurnegon” or “vurnegon”.

| ābrenka | gēlenka | embōñe |

|

|

|

| vējōñe | jurnegon | vurnegon |

|

|

|

Using the second type of ligatures and phonemes in this context is not mandatory, however, and will not occur in older texts.

It’s also worth pointing out that even though the ligatures are based on phonemes, they do not change when the pronunciation changes. For example, you can use a ligature for “īha” to make an adjective from the noun “Valyria”. If you then want to talk about a person who is Valyrian (Valyrīhy), you keep the suffix for (-īha) and add an “y” afterwards. A more formal way to depict the word would be combining the character for “woman” with the character for “Valyria” enclosed by a circle.